The legal cannabis industry appears poised to enter uncharted waters: an economy engulfed by a full-fledged recession.

The coronavirus is inflicting severe damage to the world economy, raising the specter of a major economic contraction, and some economy watchers – including Bank of America – have already asserted the U.S. is in a recession.

How would legal cannabis companies hold up in a severe downturn? Fairly well, said several industry experts.

And alcohol sales might be a good barometer.

Industry experts note that most cannabis consumers are wedded just as closely to marijuana as they are to other essentials, ranging from pharmaceutical medicines to toilet paper and – perhaps a closer industry parallel – alcohol.

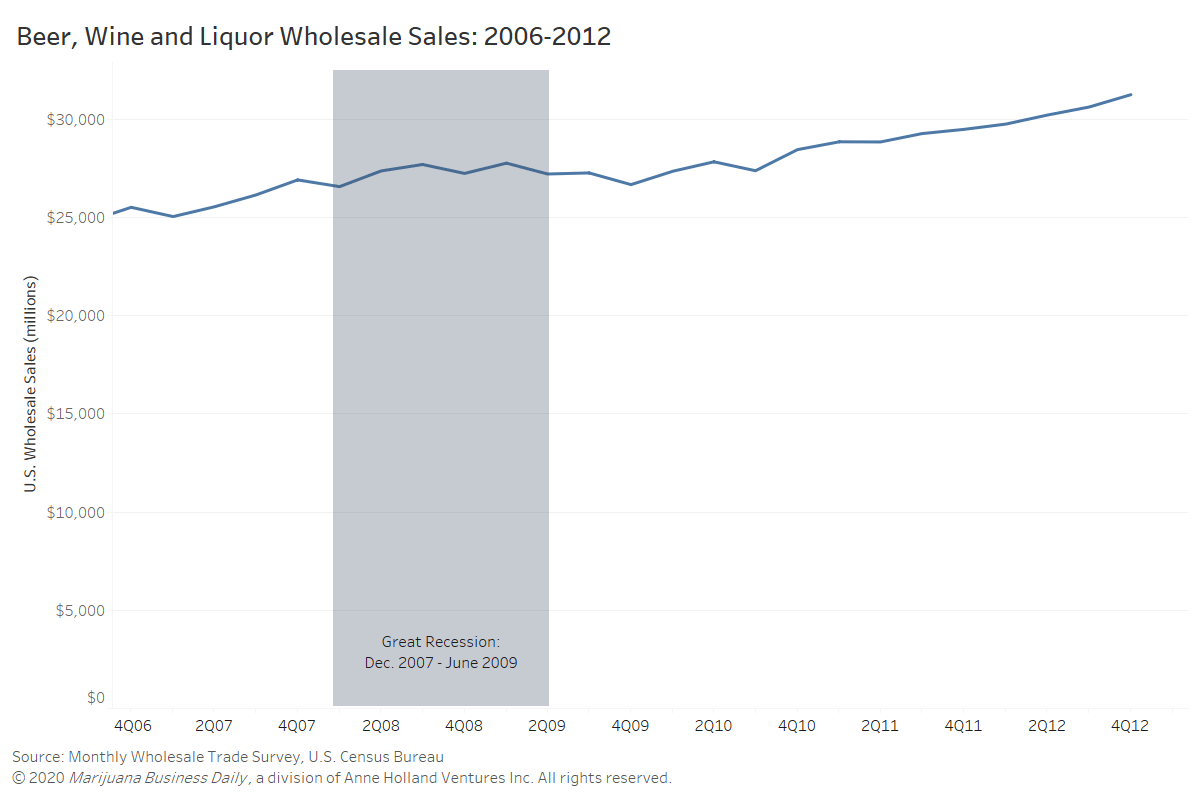

The accompanying chart shows that alcohol sales at the wholesale level held up relatively well during the Great Recession that stretched from December 2007 to June 2009.

And, over the longer term, sales increased.

The connection between cannabis and alcohol

Former Sacramento, California, cannabis regulator Joe Devlin, now senior vice president with Ikänik Farms, based in the state’s capital city, went so far as to say he believes the marijuana industry is “relatively recession-proof” because MJ has fallen into the same category as spirits and tobacco: It’s a relaxation vehicle and reward that consumers give themselves.

And it’s not something they’re likely to cut out of their budgets.

“A lot of these sin businesses – like alcohol, tobacco and cannabis – they hold up better in periods of recession than other traditional businesses,” said Beau Whitney, an Oregon-based economist who has worked for multiple cannabis firms, including New Frontier Data in Washington DC.

Whitney said that, based on his consumer demographic research, most marijuana users budget carefully for their monthly purchases, making it less likely that they’ll cut spending on cannabis instead of, say, spending less at Starbucks.

“Consumers budget for cannabis. And they will budget and spend consistently, even when they pare back payments on other things, like that latte or going to the movies,” Whitney said.

Looking back to inform the future

If indeed the alcohol industry is any guide, the cannabis industry is likely to hold up relatively better than other mainstream industries such as airlines, restaurants, entertainment, leisure and other sectors that so far have borne the brunt of the economic fallout inflicted by COVID-19.

But consumer buying habits might change in favor of cheaper cannabis products, as happened to alcohol during the Great Recession.

A 2009 Nielsen consumer survey – taken near the official end of the recession – suggested people drank less expensive beer, wine and spirits.

“When it comes to stretching their alcoholic beverage dollar, beer, wine and spirits consumers report several bargain-hunting strategies,” Nielsen noted in a news release at the time.

“While about half report not changing the way they shop for alcoholic beverages, the other 50% are actively seeking out the best deals. Across all alcoholic beverages, the most prevalent strategies include comparing shelf prices, waiting for a sale and taking advantage of other special offers.”

In other words, in tough times, it’s not as though consumers stop drinking or smoking. If anything, those habits are increased by stress.

“What does alcohol and tobacco do during a recession? It skyrockets, because people are stressed out,” said Sara Gullickson, CEO of Arizona-based CannaBoss Advisers.

Gullickson noted that no industry is completely “recession-proof,” but she argued that marijuana is much better positioned to weather an economic downturn than many other industries.

That’s a sentiment shared by Andrew DeAngelo, the co-founder of Oakland, California-based Harborside, which opened in 2006 and endured the Great Recession.

“Whenever there’s a recession, whenever there’s a war, whenever there’s a natural disaster, people need and want more cannabis, not less cannabis,” he said.

DeAngelo said that during the Great Recession, Harborside fared overall just as well with customers as it did beforehand.

“Harborside did not see any noticeable effects from the last Great Recession,” DeAngelo said. “For a certain percentage of the population, weed is just as important as food and toilet paper.”

Smaller purchases but purchases nonetheless

Consumers are still likely to change their buying habits if a recession does hit the U.S. full force, Whitney and others agreed.

Consumers “may go down a shelf, so instead of buying premium Kettle One, they may buy Smirnoff or something,” Whitney said, drawing a parallel between premium alcohol and premium marijuana. “That may be the case, that they go from top shelf to medium shelf, but they’re still going to be spending.”

Gullickson also hedged a bit and said she doesn’t want to wear rose-colored glasses so dark that she doesn’t understand “if we do hit a recession people aren’t going to spend a thousand dollars in consulting fees.”

So she’s planning for that.

She “100%” agreed that in the event of a recession the states that don’t have well-developed cannabis programs might look to marijuana as a way to stimulate their local economies.

States adjacent to ones with cannabis programs will see that, as far as tax dollars go, any of the markets with developed marijuana businesses are thriving, she added.

Labor shortages, store closures, illicit market could be problems

In California, if a particularly hard recession hits, one of the options for price-conscious consumers remains the illicit market, because state and local taxes are still driving up prices on legal MJ products.

“In places like California, it’s not that difficult to find illegal cannabis that’s 30%-50% cheaper (than the regulated market),” Ikänik’s Devlin noted. “How recession-proof is the regulated market going to be when it has to compete with the illicit market?”

Of course, all bets are off for the marijuana industry if the COVID-19 pandemic forces MJ businesses to close, which is also a very real possibility.

Several storefronts in Colorado and other states have already voluntarily closed their doors, and in many of those markets, home delivery is not yet an option.

Whitney also warned that the industry could be hit by a labor shortage, which he’s already seeing manifest in Washington state, where the coronavirus has spread rapidly. Many employees, from store managers to budtenders, have had to call off work because of school closures that forced them to stay at home to watch their children.

“We’re starting to see labor shortages impacting the industry more so than a lack of demand,” Whitney said.

Which means the industry could be put even further to the test this year, depending on how severely the world economy is disrupted by the coronavirus.