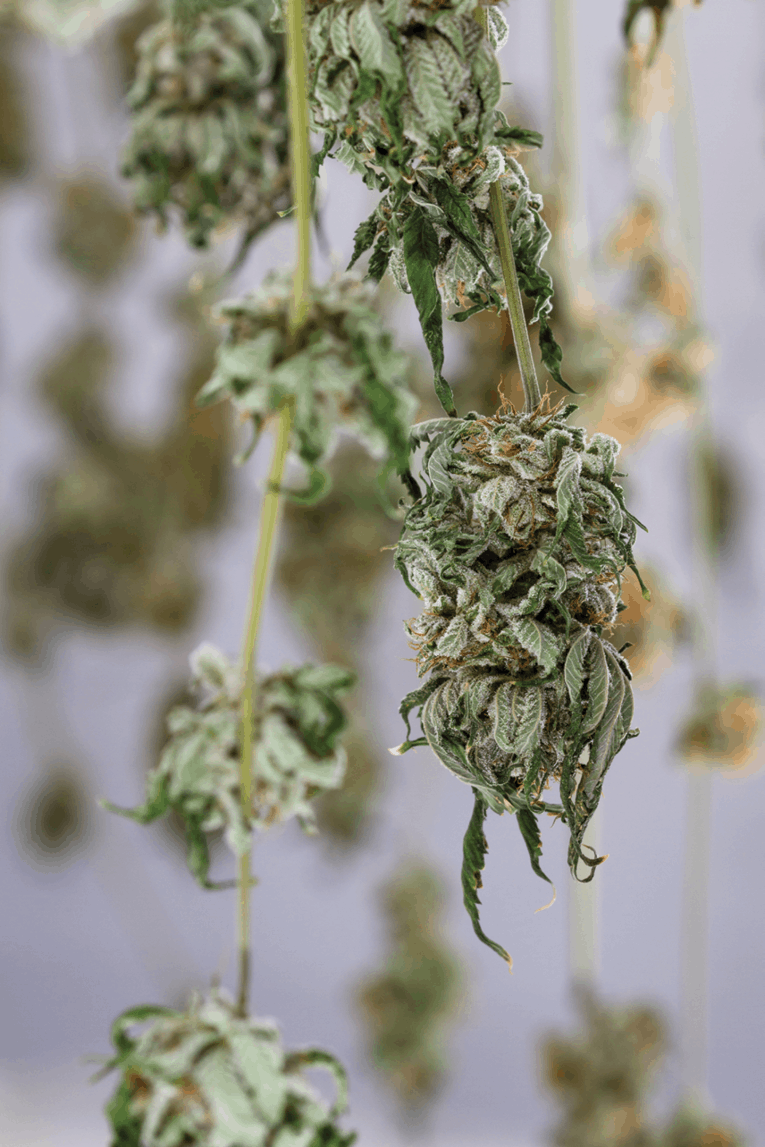

Recently, while visiting a friend, I was handed a beautiful cannabis bud. It was covered with glistening resin glands—densely covered in them, actually. The aroma was robust and very pleasant; the bud was not overly moist nor even close to being overdried. It was, in fact, perfect in all aspects.

The only “flaw,” if you want to call it that, was that the bud was not a product of the regulated commercial industry. Rather, it hailed from a grower who maintains six plants at his home (the legal allowable limit in this person’s jurisdiction). This limited canopy allows the grower to give special attention to every aspect of the small garden, including, and most importantly, to the drying and curing of the final product.

I wondered aloud to my friend whether the specimen would pass the required state testing for fungal/microbial growth given its moisture content; we both agreed it probably would fail testing standards. (Higher moisture levels increase risk of fungal/microbial growth.)

Neither of us had experienced the same moisture levels nor terpene content in commercially available product. (That’s not to say that it doesn’t exist, but just that neither of us had come across any.)

The Problem With Dry Cannabis

Overdried cannabis has less aroma and flavor (terpenes), and burns hotter and faster. The latter issues result in an unpleasant customer experience, to say the least, and typically requires that a greater amount of cannabis is consumed to get a desired experience.

When cannabis is dried too long or rapidly, it is primarily at the expense of the lighter, more delicate essential oils (terpenes). The lighter, most volatile terpenes have the lowest evaporation points and dissipate first during drying, before the water does.

In states that sometimes have a very low ambient relative humidity (RH), such as Arizona, Colorado and Nevada, it can be very easy to overdry cannabis. I’ve seen perfectly dried and cured buds from California crumble when touched after only minutes of being left on a table in a Denver hotel room in wintertime.

Of course, many other factors contribute to and influence the quality of dried and cured cannabis, beginning the moment of harvest. I’ve seen uneducated growers, who did not appreciate the nuances and delicate qualities of cannabis, take a “dry it fast, so we can sell it fast” attitude.

Others may try to dry the plants harvested on Friday alongside the harvested plants from Thursday, next to the plants from Wednesday, etc. In those situations, the released moisture from Friday’s plants gets absorbed by drier plants harvested the prior Wednesday. I also have seen drying rooms with sealed environments that only employ heaters and dehumidifiers, which makes it difficult to truly control the environment; the ability to intake fresh air and exhaust heat and moisture is also a must to properly and evenly dry large amounts of cannabis.

Drier = Safer?

Some commercial producers quick-dry their cannabis to avoid any chance of fungal or microbial growth. Contamination was a problem for the cannabis industry, especially in the earlier years of legalization. A lot of early-legalization cannabis was dried and cured the same way it had been for decades, and the moisture levels of cannabis submitted for testing also was as it was for decades, but that same moisture level now often results in unacceptable levels of detectable contaminants.

I suspect that after failing testing, some growers chose to simply overdry the cannabis rapidly to minimize the risk of infection. Some cultivators began using two-way moisture packs to rehydrate the cannabis. These packs maintain the cannabis’s moisture content by absorbing and releasing moisture to maintain a given level. The desired level can range from 54% to 65%, varying mostly depending on personal preference or how long the cannabis will be stored. (Mold and bacteria typically grow on cannabis when the moisture level is excessive (more than 65%), which can cause total crop loss.) These moisture packs also can pull moisture from wet cannabis, meaning it also can help in the drying process.

This might seem like a savvy way to work around the microbial testing issue, but the drawback with that practice remains terpene loss. By rapidly drying then rehydrating utilizing moisture packs, growers sacrifice the buds’ aromatic qualities. Once the plant’s terpenes evaporate, they are gone forever.

Small-Batch Techniques

A craft farmer obviously has much more control over small batches, which can simply be picked up and moved to any preferred environment, be it warmer or cooler, more humid or less humid, or more airflow or less airflow. Many craft growers, like other commercial growers, constantly monitor the state of their products and environments; however, it is much easier and more common for a craft grower to also treat each bud as an entity in itself—meaning large buds can be treated differently, and separately, from small ones.

So, how can a large-scale producer replicate the conditions of a home grower or craft producer that produces small batches of plants? It will require the replication of ideal drying and curing conditions on a grand scale with no shortcuts and complete attention to every detail en masse. This will also give a strategic advantage to large-scale producers who adopt these small-batch techniques to minimize terpene loss and improve moisture content.

So, what are these techniques? For starters, cultivators could and should sort cannabis flowers by size. Drying and curing large and small buds in separate bins would allow post-harvest specialists to monitor and treat each bin as its own entity and deliver to it exactly what it needs in terms of dry/cure time. Whether by machine or by employees, sorting buds by size should be a top consideration in the post-harvest process.

Also, cultivars should be dried and cured separately as, based on my experience, they can dry at different rates; and plants harvested on different days should be kept in different rooms to avoid having the evaporated moisture rehydrate drier batches. Small-batch drying methods require significant compartmentalization to be successful. Having multiple (smaller) dedicated drying areas that can constantly be fine-tuned is critical to achieve this level of terpene and moisture-content quality.

The Packaging Factor

Many other considerations exist with respect to the final product that are out of a grower’s control. For example, a grower must wait after drying and curing for the laboratory results for a given batch before packaging it, affecting the end quality. And if that product is packaged in a hot or dry environment, moisture and terpenes evaporate and the product can dry to undesirable levels.

Once packaged, some cannabis will go to a distributor. There, it can find itself on a shelf, with the grower having no control as to when the distributor delivers the product to a point of sale. Then, one must consider time on shelves at the dispensary or point of sale. Growers must ask themselves what the accumulated time from cure/harvest does to cannabis as it waits on the shelf. Some companies have begun to state the harvest date on their packaging so customers only receive the freshest products possible to ensure a pleasant customer experience and receive a quality-association with their brand/products.

That said, a company must do everything to retain as much of the favorable aromatics as possible by using sealed storage containers. For example, packaging a pre-roll in a cardboard container allows for the wicking of moisture and terpenes from the cannabis into the cardboard and, in turn, evaporate—leaving the cannabis overdried. Plastic packaging is also less than ideal, as the static charge from the plastic allows trichomes to stick to the sides of containers.

Properly sealed glass containers are the best—although more costly—option to retain both moisture and terpene content. Dark or colored glass is better than clear, as UV rays from sunlight can cause terpene degradation.

As the industry continues to advance, consumers will become more educated about cannabis and increasingly will demand higher-quality products, and those products will be composed of much more than merely THC, CBD or some other isolated cannabinoid. Customers will increasingly seek the companion qualities of incredible aromas and flavors, neither of which exist with overdried cannabis. Large-scale producers would do well to take their time and pay attention to how they dry and cure their products.

Kenneth Morrow

Kenneth Morrow